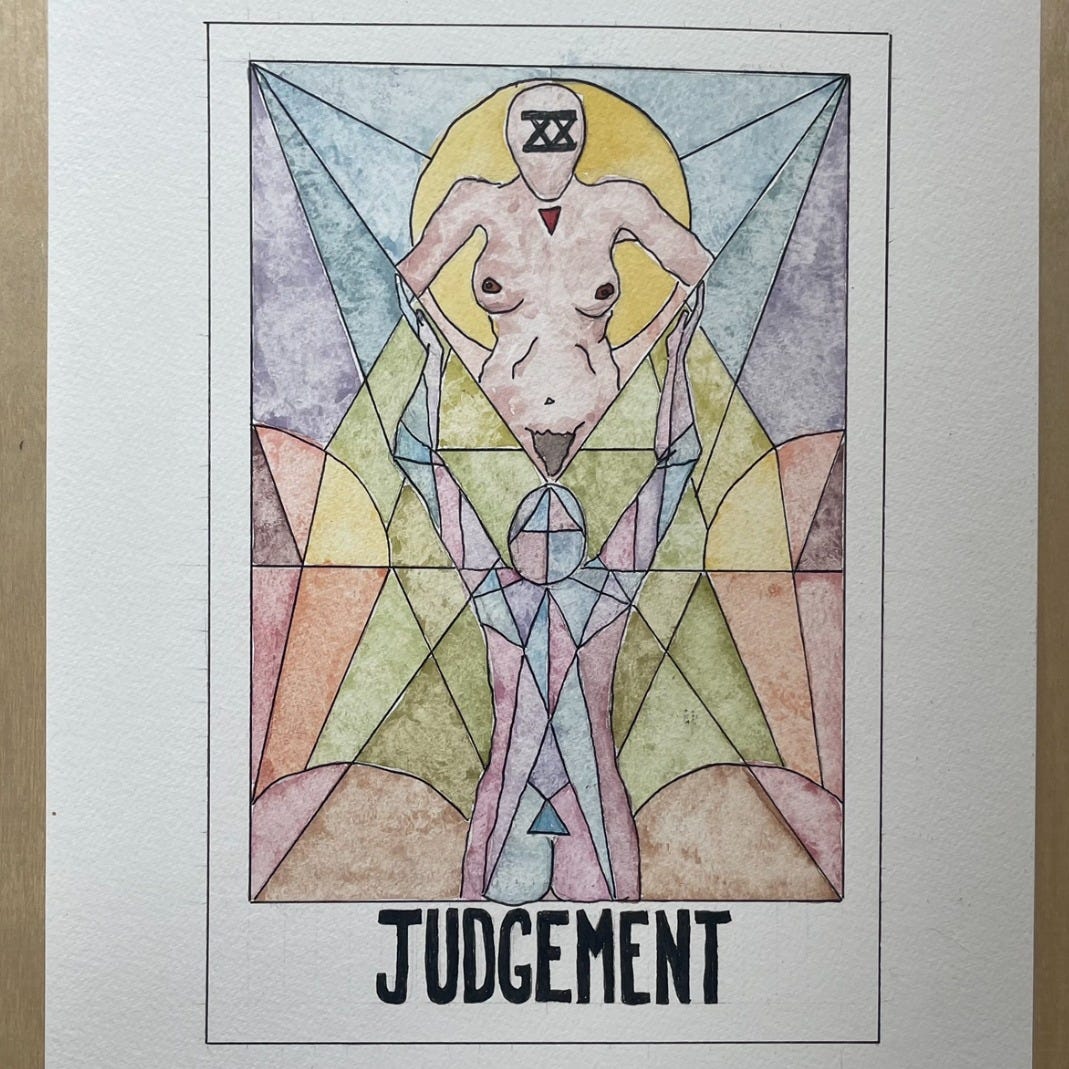

The Tarot of Songwriting 20 - Judgement

Rilke's mother, Philip Larkin and a restless horse called Legacy

unto the 3rd and 4th generation shall the sins of the father be visited

Exodus 20:5

I believe I was quite young, 9 or 10 maybe, when I recall waking up on more than one occasion with a sharp intake of breath, terrified I would fuck up my children; It sounds dramatic, but I remember it vividly.

It can’t have been till my early teens that I first read the Phillip Larkin poem This Be The Verse with its infamous opening lines: "They fuck you up, your mum and dad. They may not mean to, but they do”. One of the first decent songs I ever wrote, Tap At My Window, was based on this poem - the idea being that refusing romantic love and thereby ceasing to continue to write the story of life is the only sane answer; a little hymn to anti-natalism, written with all the worldly wisdom of a naval gazing sixteen year old from Reading. Man hands on misery to man, Larkin concludes, so don’t have kids yourself. I was surprised to find out, as I did only recently, that he was 49 years old when he wrote that; my first thought was - dude…grow up, let it go.

It was, again, only recently, reading an essay on Larkin in a collection of Martin Amis’ reviews (The War Against Cliché), that I discovered what a divisive figure he was. I’m still not entirely clear why, post-partum brain adled as I am, perhaps one of you readers can enlighten me - but what was notable was Amis attributing some of the revisionist controversy surrounding Larkin and his politics to a series of posthumously published collections of poems and letters which failed to differentiate work Larkin had never intended to be published. Some unsanctioned rotters slipped through the net of the editor. This created a lack of clarity about who he was as a poet, thereby bringing into question who he was as a person; softening him up for attack, as Amis put it.

It was this, coupled with the daunting task of being a responsible parent and drafting a will, that got me thinking about legacy. Though I’d prefer not to (or at least prefer not to admit to it), I do sometimes wonder how I am (or will be) seen, what the median answer to who I am or was as an artist would be. And now, similarly as a parent…how will that work be reviewed?

For the first few years of Rainer (born René) Maria Rilke’s life, he was dressed as a girl and referred to as Sophie by his mother. Having suffered the loss of a daughter shortly before Rilke’s birth, Frau Rilke was clearly experiencing some severe disturbances. How this early outwardly inflicted identity confusion affected the writer and in what ways it contributed to his extraordinary talents as a poet are, of course, hard to quantify. But as a frequently referred to note of curiosity among his biographies, one can’t help but conclude that it deserves a place in the bouquet of evidence that an artist is made by their cuts and grazes.

One wonders how he came to reconcile his mother's overbearing and unresolved personality. How does one pursue a healthy life against the injustices of fate or family without collapsing into despair? Perhaps the irreconcilable is the driving force behind all creative work. Perhaps artists have an instinct that the disturbances encountered or inflicted upon them in childhood can only be settled if they are reined as restless horses and put to use. Rein that restless horse and call it Legacy. Our deprivations become the spring of our desires, and desire is, of course, the force of pleasure, need and creativity. In some unfortunate instances, these are the forces that drive people mad. In his fourth response to Franz Kappus in Letters to a Young Poet, Rilke addresses this unresolvable desire as the force of life itself:

“You are so young, all still lies ahead of you, and I should like to ask, as best I can, dear Sir, to be patient towards all that is unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms, like books written in a foreign tongue. Do not now strive to uncover answers: they cannot be given you because you have not been able to live them.”

The idea that living is a slow revelation, one that, when approached correctly, produces its own desire to continue, is beautiful to me. Answers to philosophical or psychological knots within us are often untangled by time alone, solutions provided in the eternal revelation of being. For me, songwriting has been evidence of this process - the urge to write a song, whether conscious or unconscious, is usually related to the need to untie some or other psychological knot within me.

Becoming a parent is an often revelatory example of this operation in action. I have certainly found this to be true. I have also found both my pregnancies to be strangely accelerated and intense experiences of this process, making me wonder whether, by some quirk of evolution, women are raced through several hundred psychological hurdles in preparation for the task of motherhood. In both my pregnancies, I have been tormented by various states of thought, mostly my own personal shortcomings, alongside a generalised anxiety about the state of the world in general. As due dates have approached and the concept of life within me has become less abstract, through whatever fateful occurrence, my torments have softened and in both instances come to something of a resolution, one that could only have been provided by lived experience—perfect, redemptive story arcs set against the impending timeline of gestation. They’ve felt like biblical messages, venial lessons delivered just in time to prevent the spread of disturbance from one generation to another.

My own mother was the recipient of more than her fair share of fate and familial injustices. Conceived out of wedlock on the eve of the end of the Second World War, my mother spent her infant years in the various dubious standards of children's homes and foster care, before she was eventually left, aged four, with a couple of elderly family members whilst her mother sailed for Australia in pursuit of another life. It was a long and very unhappy arrangement, and she was, at times, treated with unspeakable cruelty. Consequently, and as soon as it was legally possible to do so, she left her adoptive parents and found herself alone in the Big Wide World by the age of sixteen. The details are not mine to disclose, but suffice to say, her existence in itself is remarkable.

Sixteen was the age I was when I wrote Tap at My Window. It’s also the age I left home and set off into the Big Wide World, though under entirely different circumstances. I had signed my (dreadful, as it turned out) record deal and joined Noah and the Whale as a touring backing singer. I was unknowingly mirroring something of my mother’s inheritance by choosing early independence while pursuing something of my father’s by becoming a songwriter (as he had been).

The circumstances of my mothers early life have had a profound effect on what type of person she turned out to be - she’s naturally a very good and welcoming host, for instance; our house when I was growing up (and still) was a refuge for a never-ending cast of waifs and strays - a bit like my mother herself, our family home, had a kind of chaos that put people at ease somehow. She has the birthdays of everyone she has ever met committed to memory, and if she has your address, you will be receiving a card. Wherever I have been, however alone, in the world while on tour, my mother has never forgotten to text me ten minutes before show time to let me know she is thinking of me. Perhaps this is why I have been able to be such a solitary person for such a large part of my life - I have no fear of the line going slack on the sense that I am loved; Hers are virtues cultivated in the awareness that it is possible to feel hopelessly alone in the world. Like most people, I experienced varying scales of psychological discomfort growing up, but perhaps it was in large part the security of my maternal wing that allowed me to safely rein anything too unreconciliable and transform it into something productive. She managed to transform her misfortune into my security.

What we make of our misfortunes are what we make our life, maybe even the lives that follow; this is the spirit of Judgement, in my understanding.

"The idea that living is a slow revelation, one that, when approached correctly, produces its own desire to continue, is beautiful to me. Answers to philosophical or psychological knots within us are often untangled by time alone, solutions provided in the eternal revelation of being."

...I could not agree more, and at more than twice your age, I have seen this play out time and again. I used to not trust this. I do know. I have come to rely on it, as best I can, based on my awareness and presence at the time.

They key is "correctly". Honesty is central to this. So is a kind of radical openness.

Larkin was a minor lyric poet who seemed old before his time. Rilke, for all his faults and there were many, was one of the great poets of the 20c and beyond. Compare Larkin with fellow Brit Geoffrey Hill, who died a couple of years back, a stern frequently difficult poet on several levels. A working class boy who made good academically , spoke several languages, was totally embedded in his native language, English. Still a controversial figure who never fitted in to academe. If the best critics are those like Hill, who come from inside the language: insert your own list(!), as I think they do, he was up at the top of his game. A radical voice, not in the old fashioned clunky Marxist sense, his last book even veers toward rap rhythms. As you may have gathered, I’m not a fan of Larkin. Prefer Frank O’ Hara. My canon runs from way back to Mark E. Smith through Hill…